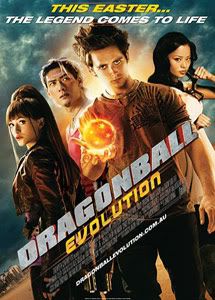

Dragonball Evolution or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Box Office Bomb

Along with being an anime buff, I’m also a big movie buff. I probably see a new film at least once a week, so I am quite familiar with the way Hollywood and the industry works. Because I have such a huge admiration for the medium, it takes a lot to make me hate a film. In fact, I’ve only hated three films within the past year while finding the 50-some other films at least tolerable.

I hated Twilight because it was a dull film that was only meant to show off a pretty boy with bushy eyebrows. I hated Mama Mia! because the film ripped out my testicles, threw them at the screen, and then sang a song about it. I hated The Legend of Chun-Li movie not because it was a poor video game adaptation, but because it was a bad action flick.

But as difficult as it is to make me really hate a film, it’s even harder to make me really love a film and make it significantly stand out for me. So when the end credits began to roll for Dragonball Evolution last weekend and I gave it a genuine applause out of admiration, that really meant something.

Yes, I actually enjoyed this live-action adaptation of the popular manga series. I was a fan of Dragonball even before I was a fan of anime. This simple story of strength, power, and domination has reached out to many Americans and has made the franchise the most popular anime ever released over here. So because I thought that the final moments of the film captured the same awesome feeling that the original comic and anime had, I felt very satisfied that Hollywood brought the property to the big screen.

But looking around, it would appear that I was the only one who enjoyed it. The Dragonball fans hated the movie before it was even made. As every photo and trailer came out, the blogoshpere would complain about how bad the movie looked and how much it was going to suck. And in the weeks leading up to the film’s release, I was bombarded with blast after blast of hate as anime fans illegally downloaded the film and watched it on their computers.

With all this negative press leading up to the film’s release, it was no surprise that the film bombed its opening weekend and only took in a dismal $4.6 million at the box office. It even undersold everybody’s already low projections.

So where did it go wrong? How did the most popular anime property in America fail to reach out to its target audience?

Sci-fi novelist Orson Scott Card offers a very interesting insight into the way Hollywood handles adaptations. Card’s 1985 novel Ender’s Game tells the story of Ender, a 8-year-old boy going to a futuristic military school to become a commander in a war against an alien race. When Card was approached by Hollywood to turn the novel into a feature film, every studio producer said they would finance the adaptation given one stipulation: they wanted Ender to be a teenager and they wanted him to have a romantic love interest.

Card was appalled at this idea. Ender wasn’t a teenager, he was only a kid! Changing that would have completely ruined one of the themes of the story. And so he refused to allow his work to be adapted until a studio allowed him to faithfully adapt his novel with an 8-year-old boy instead of a love-struck teen. And so that is why the Ender’s Game movie has never seen the light of day.

The Dragonball movie property was optioned in March 2002 and had been sitting on the back burner for many years before ever getting the go ahead to start filming. What got them that green light?

Well, I imagine it was the situation that Card was describing. The movie execs wanted the film’s protagonist to have a romantic interest, and so you’d need Goku to be past adolescence and pining for love. Once the screenwriters gave in to the movie studio’s demands, they got their financing and could finally begin filming it.

You cannot make a big-budget Hollywood film without that stupid stipulation. Hollywood feels that the only they they can guarantee box office success is if movie-going couples could make a date out of going to see the flick. So the universal rule is that you have to have some sort of romantic element to it. Even the recent adaptation of the Watchmen – one of the most faithful live-action adaptions of all time – added a cheesy romantic undertone between Nite Owl and Silk Spectre in the early scenes of the film.

Like the case with Ender’s Game, this stipulation completely goes against everything about the original Dragonball story. Goku was a goofy boy completely unaware of sexuality or romance. That’s was actually a big part of his character in the early part of the story. When Bulma and Master Roshi introduced the idea of sex to the young Goku, he is completely indifferent to it. He’s just a kid, after all. All he cares about is playing, fighting, and eating.

This asexuality becomes a theme for the entire 11-year run of the comic and anime series. Characters grow older, get married, and then have kids, but the whole time the concept of love, courtship, and sex never come up. You assume that Goku and his wife Chi Chi eventually become intimate because they end up having a few kids, but no matter how adult Goku gets, his childish indifference to love and sex still remains.

Perhaps this is one of the biggest appeals of the original series and why it sticks out so much for young American males. While Hollywood and TV keeps on throwing sex and romance towards us, Dragonball celebrated the male id’s desire for brute strength and dominance. The men of Dragonball were manly men. They didn’t need to fight to show off or impress some dame. They fought solely to survive and to become the top alpha male of the entire universe.

When Hollywood forces the screenwriters to make one of the first lines of the film be teenage Goku asking his grandfather how to pick up women, you have just alienated every Dragonball fan out there. You’ve made Goku a fragile boy who’s primary desire is not to be the strongest in the world, but to win over the heart of the young exotic hottie Chi Chi. And so with love on the brain, he begins stumbling through his fight training and screwing up key moments in battle.

In other words, Hollywood made Goku to be as much of a pussy as you, me, and everyone else in the whole world. That’s how 20th Century Fox truly blew it.

The sad thing is that you could tell that the screenwriters actually understood the original material and tried to remain as faithful to it as possible. When I put aside the romance angle to the film, I saw a Dragonball movie adapted the way it should have been. Bulma’s spunky attitude. Master Roshi’s slight perversion. Goku’s relationship with his adopted Grandfather. Yamcha being a thieving airhead. Mai and Piccolo’s cold indifference. Bulma’s expanding capsule car and dragonball tracking device. Goku transforming to a giant ape-thing. The climatic ending as Goku’s Kamehameha wave overpowers Piccolo’s to prove that he is the most powerful being on Earth.

This was the manly action that made the franchise so big in America and all around the world. This was the manly action that made 20th Century Fox pick up the rights to the film seven years ago. This was the manly action that should have brought in a lot of nerd money this past weekend. All the right elements were there and Hollywood’s big budget made it look amazing on screen. That is what I saw when I watched the film, and that is why I applauded the screenwriters’ attempts to make the best Dragonball film possible given these stupid circumstances.

By including a sugar coated romance element to it, Hollywood violated a Dragonball taboo that forced the fans to give up on the whole thing completely. Dragonball Evolution bombed like it rightfully should. Studio execs who stuck with an outdated formula for creating a box office success ended up creating one of the biggest blunders in recent Hollywood history. But if they had just simply eliminated the cheesy romantic undertone, then the movie would have been significantly better in the box office then it did last weekend.

… but then again, it probably doesn’t matter. After all, the Dragonball fans hated the movie before it was even made.