Warning: This post deals with internet flaming, so be prepared to much more salty language than what I usually write.

Last week’s Q&A section of AnimeNewsNetwork brought up a very interesting question – Just why do anime fans seem to hate each other so much? I was planning on writing on this subject because I have recently witnessed this in action and felt that it needs to be addressed. This kind of belittlement is completely unnecessary, and is even pathetic when you realize that no one else actually hates otaku besides other otaku.

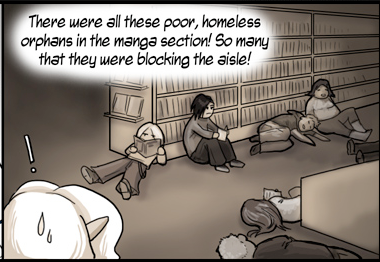

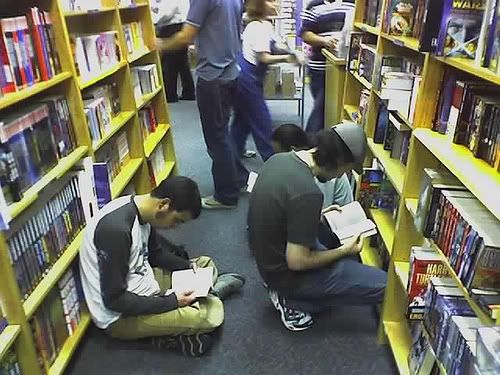

When my post about Manga Hobos made its way around the blogosphere, I got to witness once again how much hatred can be thrown around so quickly from one otaku to another. This response in particular got to me. First of all, he took some cheap shots directly at me for mentioning Ichigo Marshmallow and accused me of being a pervert over it. Well, that is nothing new, and I can defend that point another day. But then he goes into a tirade over yaoi, people using Japanese words and phrases, and somehow ends it with the Japanese invasion of China.

(I’m sure he said some other things in there, but honestly, it’s not an easy post to read all the way through.)

Yet despite this absolute hatred over anime and the American fan community, he very openly admits to being an anime fan himself! “Seriously, I’ve been watching anime for 18 years, and I spend more time on it than any of these kids. The difference, is that I have not somehow forced it into an excuse to be a social and emotional wreck.” Of course, he is far superior to the rest of those scumbags who like anime. His reasons for liking the genre are genuine while everyone else’s reasons are bullshit. And after he’s done insulting myself and every other otaku he can think of, he has certainly proved that “I’m that big of a nerd, and I’m not a fucking douchebag.”

Mr. Douchebag is the prime example of the otaku self-denial and self-deprecation. The only people who take the time to hate otaku are otaku themselves.

I’m reminded of a friend I once had some years ago in my Japanese class. He was completely obsessed with Japanese pop-culture and Japanese pop-music. And even though he wasn’t as much of a anime fan as I was, he still read my blog and thought what I had to say was very interesting.

But as time went by, he started to show a lot more hatred and disgust over anime fans, particularly those who were trying to study the language with him. He really felt that his interest in the culture was better than ours. Then one day, I mentioned to him that I had just become the president of the university’s anime club.

“Oh, you mean the club that everyone sits around an watches animu?” he asks. His voice indicated that it was meant to be a harsh joke.

“Animu?” I question him.

“Yeah, animu! It’s what all the fucking otakus say.”

“Look, I’m about the biggest otaku you’ll ever find, and I have never heard that word before.” And I really hadn’t. But I could tell that he meant it as some kind of derogatory term for anime fans, and I was very insulted by it. And so ended our friendship. For some reason, he just felt like he shouldn’t be classified with the rest of the otaku, even if he was a non-Japanese person obsessed over Japanese culture.

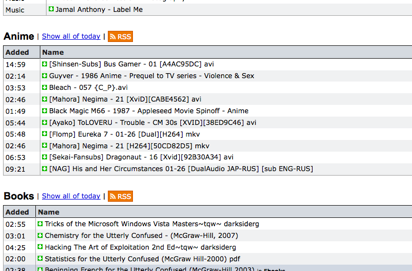

I didn’t hear the word “animu” again until I was introduced to the website 4chan.org. This is a image message board created by anime fans and modeled off of a Japanese message board. The site featured sections dedicated to many different types of anime (hentai, yaoi, yuri, pretty girls, etc), and was sponsored by otaku-merchandising websites.

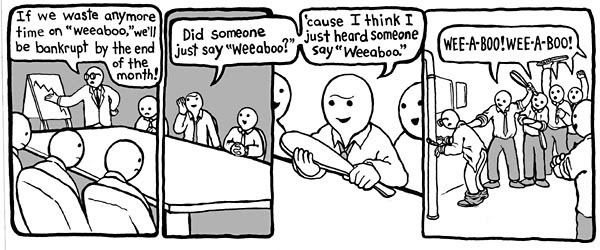

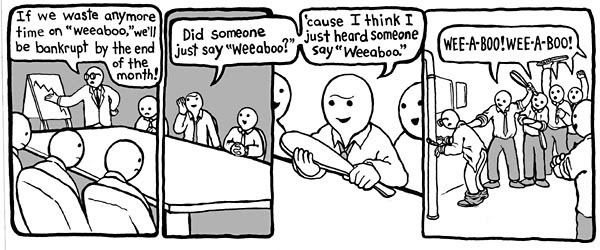

But despite this huge otaku influence on every page, a majority of the website’s visitors spent their time bashing otaku. Every time someone starts talking about anime or Japan, they get bombarded by the phrase “weeaboo”.

“Weeaboo”, “Wapanese”, and “animu” have been the only major derogatory terms I’ve heard used against American otaku. I can understand the meaning of “Wapanese” since it is a portmanteau of “white” and “Japanese”, but I cannot understand the origins of the other two or why I’m supposed to be insulted by them. When I ask, the only explanation I can get is to refer to the comic shown above, which doesn’t answer any of my questions.

And of course, the only time I hear these phrases are on 4chan or from people who visit 4chan. Since he used some of these words in the anti-otaku tirade I mentioned earlier, I can certainly bet that Mr. Live Journal Douchebag also frequents the website. But the website is the biggest hangout for otaku, so every time I hear these words, I know it comes from pure hypocrisy. This is the reason why I’ve stopped going to that site, and have been better off for it ever since.

Even with all this otaku negativity going on, the fact is that the outside world doesn’t actually hate us. If you ask anyone to describe the negative geek stereotype, the answer will may include “good at math”, “works with computers”, “into Star Trek”, “into comic books”, or “plays Dungeons and Dragons”. However, Anime and manga are not that mainstream yet, so the general public doesn’t make any negative connections with it. In fact, I’ve only had very positive experiences when talking to non-otaku people about being interested in anime. It always seems to be a topic of conversation when I go to job interviews, and I’ve even been interviewed in some local newspapers with articles talking about the trend.

The only time that I’m ever insulted for my interests and tastes in anime is from other otaku, and it is completely unnecessary. So I’m calling out to all you otaku there to please stop hating on one another!

Now I am aware that some people within the otaku community get freaked out by a certain type of otaku you’d find out there. While their numbers are limited, they really stick out among the crowd. I’ve ran two different college anime clubs in my time, and I’ve seen my fair share of them as club members. I’ve also run into many of them at anime cons. Manabu Kuchiki from Genshiken is the perfect characterization of these types of otaku.

These people obviously suffer from some kind of social dysfunction. They feel comfortable in the otaku community because the otaku community is a counter-culture by nature. It’s easy to get mad at them because their behavior can be annoying and unsettling at times, and they are the easiest scapegoats you can find. But you must realize it is not their fault. They are actually good people, and should be commended for their efforts in trying to be sociable despite their disability. Hell, I’ve always found them to be the most active and loyal members of my clubs.

And they do not make up the entire community. They do not give the community a bad name because the only people who see them act like this are already within the community. You’re also not at risk of turning into one of these socially dysfunctional otaku unless you let your fear and anger get the best of you and you start acting stupid, like Mr. Douchebag did on his Live Journal.

So why all the hate, people? We’re all in this together. No one’s reason for being interested in anime or Japanese culture is more genuine or pure than anyone else’s. You could be into shounen, shoujo, yaoi, moé, Naruto, subs, dubs, sci-fi, manga, anime, j-pop, visual-kei, gothic lolita, dating sims, dramas, j-horror, samurai… it doesn’t matter. We’re all part of the same community, and there is no out else out there hating on us but ourselves.

Update: Daniel finally clarifies the origin of “weeaboo” and “animu” for me:

There used to be a filter on 4chan (and still is, for all I know) that changed “wapanese” to “weeaboo”. Presumably there was no reason for this apart from “a mod was tired of seeing people/things get called ‘wapanese’ and decided to filter it to a random nonsense word.” And now people actually type/say “weeaboo” instead of “wapanese”. 4chan is prone to this sort of silliness; it is a silly site.

Many English words “sound Japanese” if you add a vowel to the end of them (as “thank you” becomes “sanku you”), and this is the root of “animu” — it is a joking way to say “anime”. It makes a Japanese word sound “more Japanese.”

Thanks, Daniel! (^_^)

Got a couple of more opinions on the otaku civil war. First up, Seng writes:

[…] what is an OTAKU? Well, in Japanese it means a social RECLUSE who is overly obsessed with any particular things and the kanji 御宅男 literally means one never leaves home. Otakus are mainly populated in Akihabara, Tokyo which is Mecca to all animemanga fans all over the world. Otaku is a negative outift in Japan and I don’t see why Americans are so proud to call themselves with that kind of jeer, just because it’s japanese?

I used to think that was the original reason why Americans would call themselves otaku, and I refused to use it myself because of the negative meaning behind it. But after Densha Otoko came out a couple of years and sparked the “Otaku Boom” fad in Japan, Japanese otaku also began using the word itself in a non-derogatory way. That’s when I gave up and started using the word to describe that anime/manga-loving geek community.

I still find words like Weeaboo and animu to be very offensive, but reader Baka Tanuki informs me that even those words are not always as hateful as they sound:

I will say though, that I’m not always sure if the frequent use of weeaboo and animu on 4chan is always meant derogatory. I know I use them, just to poke some light fun at myself and fellow fans, but not in a derogatory way. A lot of what is said on 4chan comes from that people like to post as if everything is SERIOUS BUSINESS and there is a “I AM RIGHT YOU ARE WRONG” attitude that stems from its anonymous nature and mob mentality. I’m sure a lot of those people couldn’t really care less; though of course, many are serious.

Thanks, guys!

I must say, the best things about attending the screening was getting introduced to the NYICFF. This festival promotes a huge number of independent, experimental, and, in the case of anime, foreign films that all target a younger demographic. I’m not quite sure how the kids handle these odd films, but as a mature movie buff, I found myself very interested in many of the films screening in NYC over the next few weekends.

I must say, the best things about attending the screening was getting introduced to the NYICFF. This festival promotes a huge number of independent, experimental, and, in the case of anime, foreign films that all target a younger demographic. I’m not quite sure how the kids handle these odd films, but as a mature movie buff, I found myself very interested in many of the films screening in NYC over the next few weekends.